egypt: cairo, luxor, and aswan - jan ’26

neon lights and grand canyon views - dec '25

This trip was never supposed to look like this. We had a prebooked December getaway to Jamaica right after my brother and I wrapped up finals week — something tropical and restorative after a long semester. Yet, just a few weeks before we were set to leave, Hurricane Melissa made landfall, redirecting the country’s energy toward rebuilding efforts. Canceling was the right decision, though it did little to soften the disappointment. Expectations were high, and suddenly we were reworking plans.

Pivoting to Las Vegas for the third time felt almost painful. Familiarity can dull excitement, especially when you are still holding onto what a trip was meant to be. We reframed the plan entirely: two days in Vegas using my mom’s Hilton package, followed by something we had somehow missed for years. The Grand Canyon.

Vegas became a starting point rather than the destination. Since the Strip felt repetitive, we focused on experiences we had not done before. We visited the Arte Museum, which felt like a weaker version of teamLab in Tokyo and not something I would recommend. In contrast, Ka by Cirque du Soleil delivered exactly what Vegas does best: immersive, dramatic, and worth seeing once. Those two days felt contained, a modern pause before the trip shifted toward older landscapes and slower forms of travel.

We drove to Williams, Arizona, a small town shaped by railways and Route 66. Its preserved storefronts and signage reflect an era when cross-country travel depended on dependable roads and stops built for passing travelers. We boarded the Grand Canyon Express, a route first established in 1901, and from the moment the train pulled away, the pace changed. Long stretches of desert unfurled outside the window, echoing the same views early visitors would have seen more than a century ago.

Our train attendant had worked with the Grand Canyon (first the park, and now the Railway) since 1991. She shared stories from decades of guiding visitors through this landscape (and one of an almost-robbery at the Hopi House) and mentioned that she had once been a Fred Harvey Girl, part of a program that helped define hospitality along America’s western rail lines. The history felt present rather than preserved, carried forward through people rather than plaques.

At the South Rim, we had lunch at the Fred Harvey House overlooking the canyon. The museum inside offered context on the Harvey Girls and the role they played in shaping early tourism in the American West. I was especially taken by the work of architect Mary Colter, whose designs intentionally mirror the surrounding geology rather than compete with it. Even the crockery at the Fred Harvey House remains original, reinforcing how much of this place has been carefully maintained.

Seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time was surreal. Standing at the rim, the scale was impossible to fully process, a landscape carved over millions of years, long before rail lines, highways, or itineraries existed.

Afterward, we drove to Phoenix to fly home, following long, open roads through desert stretches dotted with towering cacti. In the end, neon lights gave way to canyon views, and a trip that almost did not happen became one defined by history and quiet awe.

central europe highlights - aug ’25

This summer, I traveled with my grandparents and family on our first multi-country trip through Central Europe, a 10-day journey that felt both special and overdue. I usually travel fast. My itineraries are dense and optimized, almost competitive. I like knowing I have seen everything I was supposed to see. Travel, for me, has often resembled a checklist.

This trip disrupted that instinct. My grandparents move at a slower pace now. Long walking days are not realistic, and plans naturally bend around rest, cafés, benches, and train schedules that do not reward rushing. At first, it felt like something was being lost. Fewer sights, fewer steps, fewer boxes checked. Yet, over time, the slower rhythm began to feel intentional rather than limiting.

We began in Prague, arriving by train, already one of my favorite ways to enter a city. Watching the countryside blur past the window felt like a transition rather than an abrupt arrival. Prague revealed itself in layers. Cobblestone streets, pastel Baroque facades, and the steady scent of chimney cakes. At the Astronomical Clock, a crowd gathered for the hourly procession, only for the moment to be over in seconds, which somehow made the whole ritual feel more human. We visited Prague Castle and St. Vitus Cathedral, and drifted down the Vltava on a river cruise beneath the Charles Bridge, where statues worn smooth at the base showed exactly where generations of people had paused before us.

Vienna felt altogether different. Polished and structured, almost like an open-air museum. We toured the Hofburg Palace, including the Sisi Museum and Imperial Apartments, and spent time in the Austrian National Library. I learned that the library once served as a private collection for the Habsburg emperors, which made the quiet feel intentional rather than imposed. Walks through Stadtpark led us to the Strauss monument, and afternoons naturally softened into coffee, Sachertorte and naps at Burggarten.

Budapest introduced a new texture to the trip. The city came into focus at dusk, with the Hungarian Parliament Building glowing along the Danube and Fisherman’s Bastion and Matthias Church offering wide views from above. We walked through Heroes’ Square, and wandered Vajdahunyad Castle, which I learned was originally built as a temporary structure for a millennial exhibition. One evening, my brother and I split off on our own for the first time.

That night, we found a small restaurant while my grandparents opted for Indian takeout back at the hotel. I ordered Hungarian chicken paprikásh, which stood out as one of the most memorable meals of the trip. Being out with just my brother added a different rhythm to the evening, a reminder that traveling together does not require doing everything together.

A half-day trip to Szentendre brought colorful art streets, ceramic studios, and a calmer riverside pace. The town was known for its artist colonies, which explained why so many studios seemed open even on a quiet afternoon. Back in Budapest, we climbed Gellért Hill at dusk and watched the city light up bridge by bridge.

We returned to Prague for our final night by train, crossing the Charles Bridge one last time before saying goodbye over coffee at Café Savoy, a place that once hosted writers and politicians in the early 20th century. It felt complete in a way I did not expect. I know I will return to these cities. My grandparents likely will not.

This trip shifted how I think about travel. A lighter itinerary did not make the experience smaller. What ultimately stayed with me were the train rides, shared meals, and the space built into each day.

vietnam, thailand and cambodia - may '25

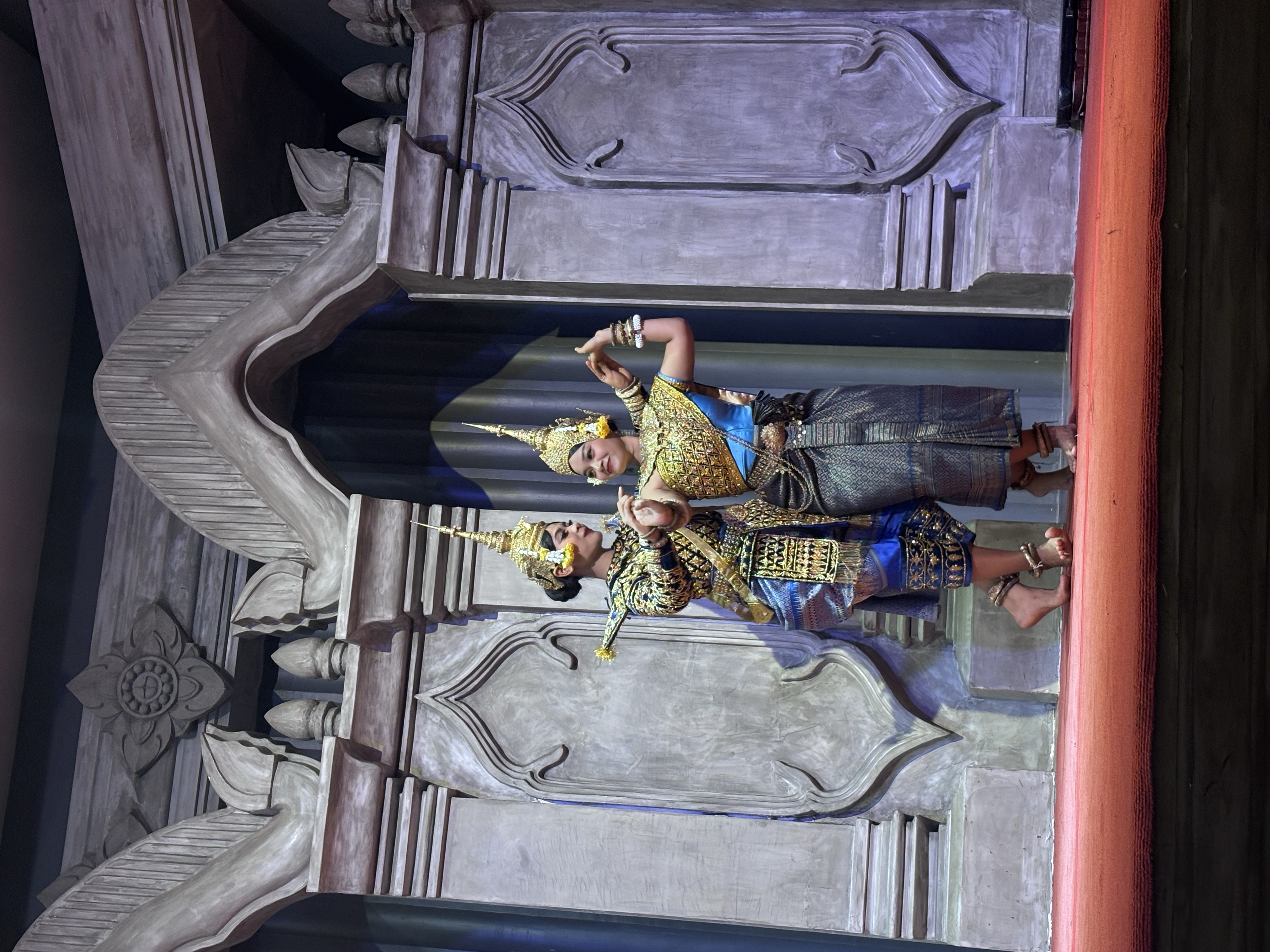

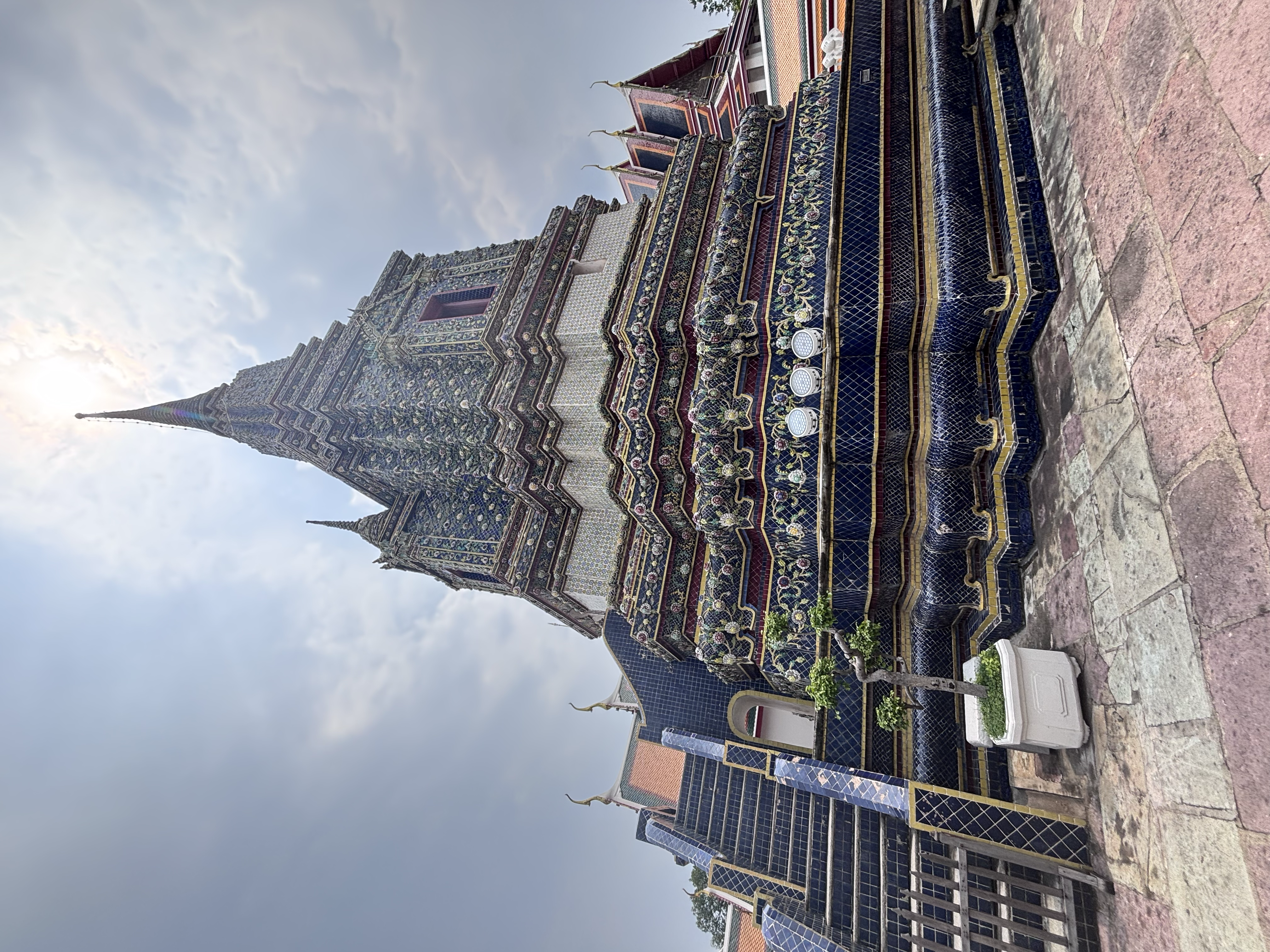

I joined a solo travelers’ backpacking group for two weeks, stepping into a version of travel that felt unfamiliar and grounding at the same time. Being on the road with strangers strips things down quickly. There is no shared history and no fixed dynamic, just people moving together for a short stretch of time. We started in Bangkok, where days unfolded through cruising the Chao Phraya River, wandering Chinatown, getting lost on local buses, and lingering over street Pad Thai and Thai tea. Visiting Wat Pho and day-tripping to Ayutthaya added moments of stillness and scale, reminders of how much of Thailand’s daily life is built alongside centuries of history. Somewhere between stops, fresh rambutan and mangosteen became part of the daily rhythm: small comforts in a city that never really slows.

Cambodia was the part of the trip that stayed with me the most. I spent nine days there, moving between the quiet enormity of Angkor Wat near Siem Reap and the emotional weight of Phnom Penh. A 4 a.m. wakeup for sunrise at Angkor Wat felt almost procedural, the temples emerging slowly from darkness as they have for centuries. Learning that Angkor was once the center of one of the largest pre-industrial cities in the world made the scale harder to dismiss as just visual. Later, visits to S-21 and the Killing Fields were sobering in a way that demanded time and silence.

At the Killing Fields, history felt unfiltered. Human remains were still visible in the ground, and bone fragments surfaced after rainfall. Visitors were asked not to disturb anything, while monks and staff periodically collected exposed remains and placed them into large memorial containers. The process was handled without ceremony, not out of disregard, but because this reality has been lived with for decades. The absence of dramatization made it more unsettling. It was clear that this was not a closed chapter, but something still physically present.

There were moments of contrast throughout Cambodia. Trying chili-fried crickets in Phnom Penh, unwinding on the beaches of Koh Rong, and hiking up to Chambok Canyon, whose calm felt almost unreal after the heaviness of the city. These shifts did not cancel each other out. They existed side by side, much like the country itself.

What grounded me most in Cambodia was the people. Our tour guide, Kosal, was a local from Siem Reap, and over the course of the trip, his story reshaped how I understood everything around me. He spent his childhood helping his parents fish and farm, earning a living instead of attending school until he was nineteen. Eventually, he enrolled in English classes through New Hope, where he learned the language that later opened doors for him. That path led him to meet his wife, build a life, and work as a tour guide. He spoke often about his children and his insistence on sending them to private English school, not out of status, but out of belief in what education can change.

We visited the New Hope Vocational Training Restaurant, an initiative supported by G Adventures that provides skill-building opportunities to marginalized community members. The project also funds a free community school and health center run by locals. Eating there felt different. The food was excellent, but the context mattered more. Later, we shared a meal at Phila’s house, where proceeds support the education of underprivileged children in the area. These were not abstract ideas about development or impact. They were immediate and personal.

One night in Chambok, I stayed with a local farming community, another reminder that the most grounding travel moments often come without spectacle. I visited a traditional two-story straw cottage in the countryside, where lunch was served on the floor. Noodles and lemongrass-coconut chicken never tasted better, not because of novelty, but because of the care behind the meal.

After returning home, I told a professor at Berkeley about the trip. He mentioned that he had traveled to Cambodia around the same age, and that it stayed with him decades later. What he remembered most was his tour guide, who was his age and not in school. Hearing that made something click. It explained why Kosal’s story lingered with me, and why Cambodia felt heavier and more lasting than I had expected. Seeing someone so close in age, shaped by a completely different set of circumstances, reframed the experience in a way I am still processing.

After Cambodia, I spent three days in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, easing back into motion and noise. I shopped nonstop at Ben Thanh Market, Saigon Square, and Takashimaya, and wandered Book Street when I needed a pause. The War Remnants Museum was sobering in a more curated way. Comfort came through routine. Egg coffee at Little Hanoi, banana pancakes with extra Sữa Ông Thọ made by my hostel hosts, and the small victory of crossing the road without getting run over all felt earned. I was especially proud of navigating an hour-long local bus ride to the airport on my own.

Looking back, this trip mattered not because of how much I saw, but because of when I saw it. Some experiences leave an imprint because they meet you at the right moment. Cambodia did that for me. I do not yet know how it will shape the way I move through the world, only that years from now, it will still be part of how I understand it.

japan - mar '25

I spent my 20th birthday week in Japan, averaging over 30,000 steps a day, eight Shinkansen rides, and twenty-two local trains. Looking back, it felt like a deliberate kind of motion, as if I was testing how much I could take on and still feel present. It was fast, imperfect, exhilarating, and deeply formative.

I landed in Osaka and almost immediately met up with strangers I had connected with through an online forum. What could have felt risky or awkward turned into one of the highlights of the trip. We wandered the city together, laughing over shared confusion and late-night plans, and it struck me how easily travel collapses distance between people. Osaka felt generous and alive, with open kitchens, bright signage, and a casual confidence that has earned it a reputation as Japan’s kitchen. I took a day trip to Nara to watch deer roam freely through the park, a tradition tied to their status as messengers of the gods, savor matcha ice cream, and explore Todai-ji, where the scale of the Great Buddha made everything else feel temporarily small. Evenings buzzed with the energy of the Namba markets, where I devoured octopus takoyaki and felt, for the first time, fully untethered in a new place.

The next day, I caught the Shinkansen to Hiroshima, then a ferry to Miyajima. Along the way, I squeezed in thrift shopping at Mode-Off and stocked up on discounted skincare at Matsumoto Kiyoshi, small routines that made the trip feel personal rather than curated. I accidentally fell asleep on a bus and ended up in Waratenjinmae, a detour that forced me to let go of control. Because of it, I missed seeing Kinkaku-ji, which frustrated me at the time but later became an easy reason to return.

Hiroshima was deeply moving. The Peace Memorial Park and Museum grounded the city’s present-day calm in its history without overwhelming it. I ate Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki, layered rather than mixed, watched the sunrise over Hiroshima Castle with melon bread from 7-Eleven, and later stood on Miyajima Island as the tide rose around the floating torii gate at Itsukushima Shrine.

Kyoto offered a different kind of stillness. Walking through the bamboo forest felt carefully maintained, almost deliberate in its calm. I did not see Kinkaku-ji on this trip, and Mount Fuji remained hidden behind thick fog, something I kept expecting to glimpse but never did. It was frustrating in the moment, and it changed how I moved through the rest of the trip. I stopped waiting for specific views to appear and focused more on where I actually was.

I visited Kamakura and Enoshima shortly after. In Kamakura, the Great Buddha sat quietly in the open air, unguarded and accessible in a way that felt different from the formality of larger temple complexes. Enoshima was especially memorable because it offered wide ocean views where I had hoped to see Mount Fuji. The mountain never appeared, but the island itself stood on its own, with steep paths, shrines tucked into cliffs, and the constant sound of waves.

By the time I reached Tokyo, I was moving with more confidence than I had at the start of the trip. I explored Asakusa and Senso-ji Temple, wandered through Ueno Park, and shopped without restraint. Nakano Broadway pulled me into its maze of vintage toys and niche collectibles, while a bowl of ramen in Harajuku fueled an evening in Shibuya. I stood at the crossing watching the city surge around me before ending the night with late-night sushi.

Turning twenty in Japan marked a shift I did not fully recognize at the time. Navigating trains, meeting strangers, getting lost, missing landmarks, and finding my way again made independence feel real rather than abstract. Japan did not just introduce me to travel. It showed me the version of myself that travel would continue to shape.